Goodwin’s Law: How Britain’s Political 'Elite' Seek to Distract From Their Own Power

The longer a debate continues, the greater the likelihood is that the side with actual power will accuse the side with none, of being part of the 'elite'

There’s an old adage from the early days of the internet which suggests that the longer an online discussion continues, the greater the probability that somebody will mention the Nazis.

This truism, known as ‘Godwin’s Law’ after the American lawyer who first coined it, now has a far more modern equivalent in British politics.

This updated version, which I will call ‘Goodwin’s Law’ after the one-time academic, turned anti-woke warrior, Professor Matthew Goodwin, states that the longer an online debate continues, the greater the possibility that the side with actual power will accuse the side with none, of being part of the ‘elite’.

No-one has more perfectly demonstrated this than Goodwin himself, who this week toured the nation’s television studios in order to promote his new book about what he calls the “new elite” now governing British life.

If you’ve somehow missed Goodwin’s thesis, you might assume that the “governing class” he refers to is the actual Government that has been in charge of the UK for the past 13 years, as well as its extensive network of financial and media supporters.

You might even assume that it includes organisations like the Dubai-based investment firm Legatum, whose think tank arm currently employs Goodwin himself.

However, you would be wrong.

For Goodwin, the actual people running the show are the “radical woke middle-class liberals” which make up Britain’s “new elite.”

As he explains in his promotional piece for The Sun, these include:

“The increasingly political celebrity class, like Carol Vorderman and Gary Lineker, the legal activists who argue their profession should no longer be impartial, or prominent left-leaning journalists, like Emily Maitlis, Jon Sopel and others, who similarly shape the national conversation around a particular set of minority values. Rory Stewart and Alastair Campbell. Almost any Radio 4 presenter.”

So while you might have assumed that Rishi Sunak, Boris Johnson, Theresa May and David Cameron have been in charge of the country for the past decade, it has in fact been under the all-seeing Machiavellian control of a shadowy elite, headed by the former presenter of Countdown.

Of course it’s easy to mock such nonsense, which is exactly why I have, but there is actually a serious point here.

In recent years there has been a co-ordinated attempt by people in powerful positions, to accuse anyone who dares to question that power, of being part of an ‘elite’ that is wildly out of touch with the actual public.

This strategy was first trialed during the Brexit referendum, when Boris Johnson and his media supporters waged a campaign against so-called ‘elite’ Remainers.

At the time this was a hugely successful strategy, in large part because it had at least a grain of truth to it. The Remain campaign at the time was led by the Prime Minister, his government, the opposition, most business people and trade unions. Attempts to paint these people as the ‘elite’ were therefore not difficult, even if those leading the Leave campaign were equally as much of a part of that elite as those who opposed it.

However, since Cameron was replaced, and since Brexit was actually enacted, Johnson and his successors have continued to use these tactics, despite the fact that they are now very much in power and despite the fact that both of the major political parties back the status quo on Brexit.

Of course pursuing an anti-establishment message when you are the actual establishment inevitably poses some difficulties, as Johnson eventually found out at the end of his premiership.

This is especially the case when the people most keen on attacking the ‘elite’ are so obviously part of that elite themselves. Whether it’s Eton-educated politicians like Boris Johnson and Jacob Rees-Mogg, or their social equivalents running newspapers like the Daily Mail and The Sun, attempts by the actual elite to distance themselves from their own power and status have become increasingly less convincing.

For these people, Goodwin’s theory obviously has a great deal of appeal.

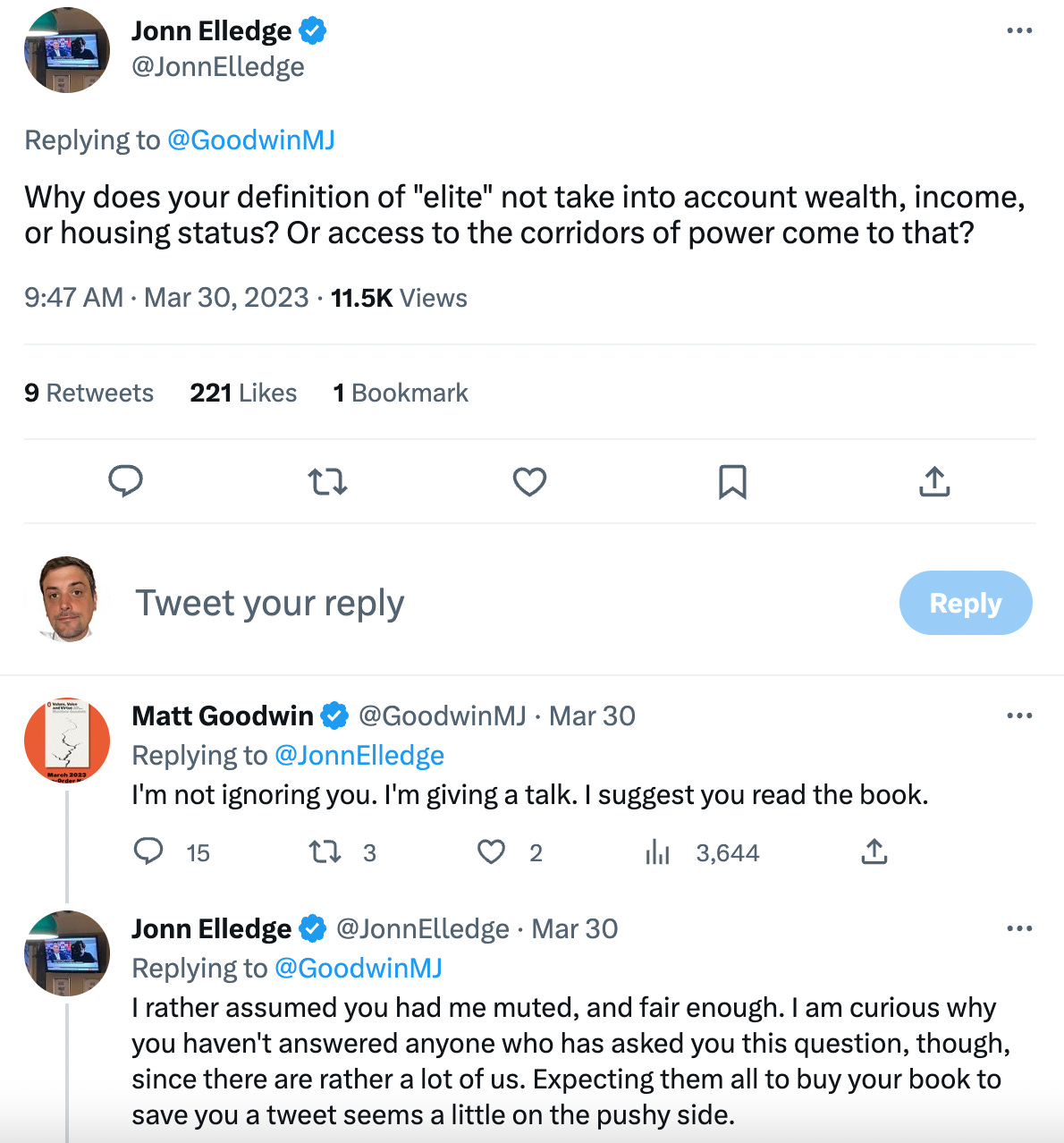

However, trying to construct an actual academic basis for such a flimsy theory is difficult, as Professor Goodwin’s rather awkward attempts this week clearly demonstrate.

As a result some shortcuts are inevitable. For Goodwin, who first made a name for himself through his attempts to paint Brexit as some sort of grassroots popular revolt, rather than one backed by some of the most powerful people in the country (including Goodwin’s own current employers) the need for academic rigour appears to have been gradually sacrificed.

So while he now claims that Gary Lineker and other members of this supposed “new elite” are wildly out of touch with the public on issues like immigration, he ignores almost all of the evidence showing that public opinion is actually far more nuanced than his caricature suggests.

Meanwhile his own ‘People polling’ operation, which is conducted for the benefit of the similarly Legatum-funded GB News channel, is used to add intellectual and academic heft to what, is in reality, a fairly transparent attempt to deflect blame from those people with power, to those people without.

So whether it’s desperate refugees on small boats, or the handful of celebrities who dare to use their platforms to support them, Goodwin’s ‘new elite’ bears little resemblance to the actual people who have been in charge of the country for the past 13 years.

For this reason, Goodwin’s work is already receiving a lot of attention from those who most stand to benefit from his theory. In one review in the Times, which describes his book as “forceful”, the former journalist turned Conservative think-tanker Sebastian Payne writes that “the fundamental thrust of Goodwin’s argument is right,” even if he does admit to finding some flaws in his arguments.

Such flaws are unlikely to receive much attention, however. As long as there are think tanks and media organisations with pockets deep enough to fund and promote the idea that the actual people with power in the country do not have enough of it, then Goodwin and people like him are likely to remain gainfully employed.

Yet for anyone without such dishonest motivations, Goodwin’s arguments should be treated with the disdain they really deserve.

Goodwin's own endless "prolier than thou" protestations can't hide the fact that, as you suggest, he himself is a fully paid-up (an indeed extremely well paid) member of the real elites that govern this country (in his case the Murdoch and Rothermere press, GB News, Legatum and Policy Exchange). But he's also employed by an institution - the University of Kent - which embodies, or is at least supposed to embody, all the liberal values which he so despises. The same institution also harbours Frank Furedi who, as Jon Bloomfield and David Edgar pointed out in a recent Byline Times, is now running a "think tank" promoting the ideas of Viktor Orban. It goes without saying that if the university was employing people as far to the left as these people are to the right, the Sun, Mail, Express and Telegraph would be in daily uproar - but leaving that aside, one does wonder what its position is on employees who publicly attack the very values on which universities are supposed to be founded. Bringing the institution into disrepute is a sackable offence in a university, and I'm sure I'm not alone in thinking that Goodwin is doing just that. But perhaps I'm just being old-fashioned, and in the modern university, raising its public profile is all that matters - no matter by what means and to what ends.

I’m bemused by The Sun article since Vorderman and Lineker are not mentioned in his book and Campbell only gets a single passing mention. I can only assume the subbies gussied it up to suit their audience. I recall writing a piece for The Economist years ago which, when finally published had been virtually rewritten so it doesn’t surprise but even so, this seems extreme. As an aside, the book makes arguments that helped me make sense of the Brexit vote. I’m sure it’s not the complete picture but a disaffected majority who voted against makes sense as contextualised by Goodwin. It’s what scares the bejesus out of Labour planners, almost as much as the ‘don’t knows’ that Goodwin routinely finds and which is reflected among past hard core Labour voters I come across. Long story short, IMO it’s dangerous to wholly dismiss a person simply because their political leanings are adrift from one’s own. For me, the bigger issue is the extent to which intolerance of other positions at both ends of the political spectrum is making our political discourse almost impossible to navigate without the danger of ridicule or ‘cancelling.’