The Shipman delusion: Why 'impartial' political journalism is often anything but

"If you believed something different you wouldn’t be sitting where you’re sitting..."

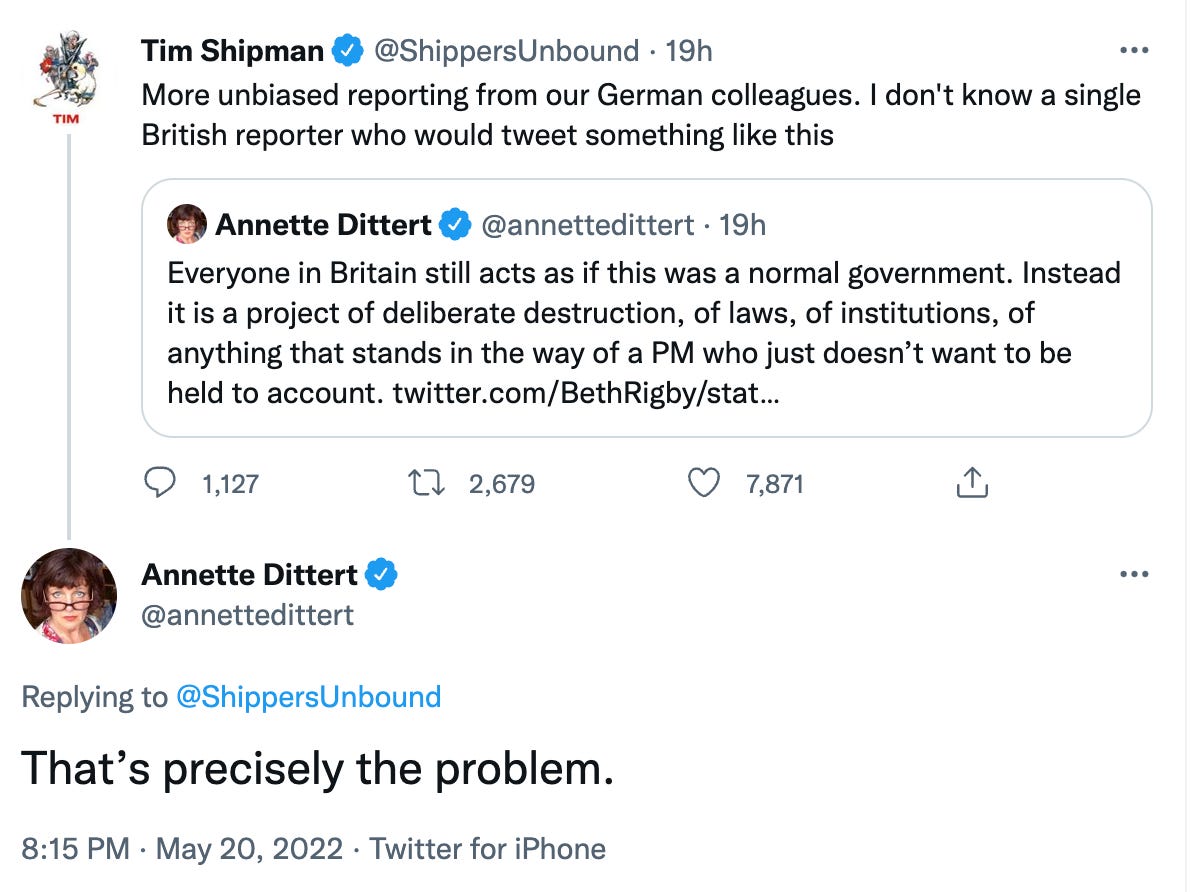

“Anyone in papers would tell you that editors, still less proprietors, almost never tell anyone what to write,” the political journalist Tim Shipman wrote on Saturday.

“It’s a fantasy of the conspiracy minded. I generally write everything I can prove. Yes, people in power have the chance to feed into that but I decide what I write.”

This idea that journalists are entirely unhindered by their editors, employers, and subjects, is a popular one within the trade.

For many it has a comforting ring of truth. Although editors may commission certain stories or comment pieces, it is rare for them to explicitly instruct us what to write.

Yet, while there may not be a direct unbroken line between the editor, or owner, and the words on the page, it is naive to suggest that there is no relationship between the two.

Shipman may feel unhindered in his day-to-day work, but the fact is that he was hired on the expectation that he would produce certain types of stories, with a certain political slant. Were he to stop doing so then he would quickly find himself out of a job.

And by political, I do not mean party-political. I have no idea how Shipman votes, if indeed he does, nor do I think it matters.

What I mean is that his view of which stories are important to tell, and which are not, is essentially a political one. He is not, as he implies, a simple channel through which events in Westminster flow unimpeded by his own bias onto the pages of the Sunday Times. He is constantly making choices and those choices are political choices.

One of the biggest choices he makes is to judge that what really matters is personalities rather than policies. Shipman’s writing, in both his weekly articles and his books, appears to be guided by the view that what really matters is who is up and who is down in Westminster.

Through the heavy use of colourful anonymous quotes, Shipman is accomplished at turning what might otherwise appear to be quite unremarkable internal disagreements and rivalries between ministers into a gripping weekly soap opera.

Another choice he makes is to portray politics as being essentially a game that is played between those personalities. Anyone who reads Shipman’s books about the Brexit era will struggle to find much serious analysis about the causes of the UK’s exit from the European Union or its impact. What you will find is lots of entertaining colour about the main characters in the drama and how they chose to act.

By portraying politics as a game, or a soap opera, with a rotating squad or cast, Shipman is making an essentially political choice about what matters and what doesn’t.

Again, I am not trying to minimise the importance of such journalism. However, what I am saying is that it is based on a particular view of the world, and the people who run it, and it is a view which is largely shared by his employers.

Needless to say this is not the only way that politics can be viewed. Another way of viewing politics is as a series of shifting ideologies and socio-economic forces which are fought-out between competing demographic groups, which politicians in turn seek to exploit.

If that sounds quite wooly it is because it is. Although history books are full of what are portrayed as long-running trends, life is often just a mess of contradictory, if not entirely random, events. Often the only reason we look back on political events as having a coherent guiding narrative is because of the story-telling skills of people like Shipman himself.

Yet some political trends do exist and they are the result of choices taken by politicians themselves. Margaret Thatcher’s decision to sell-off the UK’s council housing stock, or Tony Blair’s decision to get millions more young people into universities, were deliberate political choices that have had deep long-lasting impact on the country.

The impact of those two decisions could be seen clearly in the results of this month’s local elections, and will continue to shape our politics for decades to come.

Similarly, while Brexit was in some respects a game played out between David Cameron, George Osborne, Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage it was also a seismic event which has impacted all of our lives and which we are still trying to understand some six years after the vote took place. By prioritising discussion of the former over the latter, Shipman is making a political choice.

Of course there are some journalists who specialise in writing about such deeper trends. Stephen Bush from the Financial Times is one good example of somebody who is expert at explaining the historical and political ties between economics, politics and elections.

He is also a good example of somebody who does genuinely try to understand their own biases and blind spots as a journalist. His annual audit of his political predictions should be a model for other journalists wishing to improve their own analytical skills.

Yet Bush remains very much an outlier. By and large political journalism in this country is shaped by what we can call the Shipman model. This model sees the main priority of journalism as reporting on what is happening inside the ‘King’s court’, rather than explaining what is happening outside of it.

However, this model comes at a cost. Like a war reporter who requires the protection of the soldiers he is embedded with, such access shades how the reporter views the ‘All Out War’ they are reporting on.

This emphasis on access is why senior political journalists often either come from the particular faction they report on, or go on to join it afterwards.

The revolving door between the lobby and government communications is not a new trend, but it has become increasingly obvious in the social media era. Having existing close links to senior government figures is often the best way of launching a successful career in political journalism. It is also incredible useful if, like some political journalists, you wish to go on to a career in corporate lobbying afterwards.

Shipman is not in this bracket. He is a skilled story-teller, who I don’t believe is actively campaigning for one faction or another.

Yet there is a reason why the model of journalism he embodies is so popular with the owners of papers like the Sunday Times. And the reason is that it does not in any way challenge the existing order.

Because when Shipman says that no editor or proprietor tells him what to write, he is likely telling the truth. Yet the reason that no such instructions need to be issued is because he is doing exactly what is expected of him.

As Noam Chomsky once told Andrew Marr, it is not that political journalists are censored by editors, or even that they censor themselves. Is is that such censorship is simply not required, if your view of the world is already in complete accord with your employers.

“I’m not saying you’re self-censoring,” Chomsky told Marr.

“I’m sure you believe everything you say. But what I’m saying is if you believed something different you wouldn’t be sitting where you’re sitting.”

I believe Lord Thomson was the last proprietor who kept his hands off The Sunday Times. Produced the great Harold Evans as editor who created the insight team of investigative journalists.