The Myth of Conservative England

The political battleground in England is changing rapidly and politicians and commentators risk being left behind

The historic dominance of the Conservative party in England under first-past-the-post has led some to assume that it is essentially impossible to win a general election while pursuing any real left-wing policies.

A version of this argument was pursued by Robert Shrimsley in the Financial Times this week.

In a piece titled ‘Keir Starmer’s conservative path to power’ Shrimsley seeks to explain and justify the Labour leader’s abandonment of his previous campaign pledges, by suggesting that he is merely “shifting policy positions to match the values of target voters”.

“If you want to understand how conservative Britain really is, take a look at Keir Starmer’s speeches…” Shrimsley writes.

“His policy positions and pronouncements increasingly acknowledge that the UK is a small-c conservative country.”

But is England really the innately conservative country that Starmer and Shrimsley appear to believe?

The argument for this is based largely on recent general election results. The Labour party has lost several elections in a row while pursuing ‘left wing’ policies, so the suggestion is that those policies must all therefore be unpopular.

But are they really? While it is certainly the case that on some issues, such as law and order, public opinion can reasonably be described as inherently conservative, on other issues that is very much not the case.

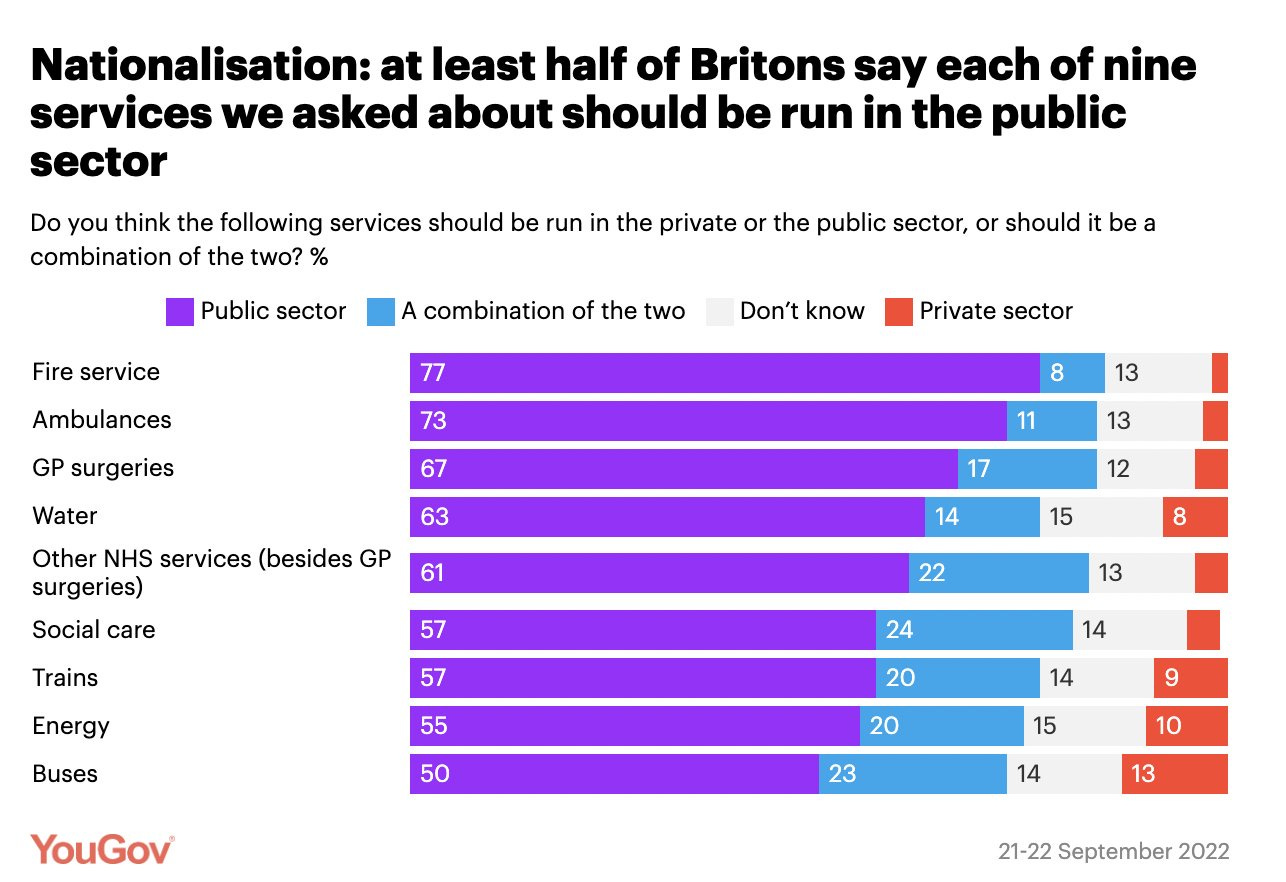

In fact if you look at polling about public spending, taxation, nationalisation, Brexit and even electoral reform, the UK public is significantly to the ‘left’ of both the current Government and Keir Starmer.

England’s supposed innate conservatism is also not evident on social issues, where despite all the recent noise about ‘culture wars’ polling evidence suggests we are increasingly among the most tolerant and open-minded countries in the world.

Whenever such evidence is raised, the response from some commentators is to say that such support for progressive policies must either be “shallow” or even some sort of mirage.

The argument then tends to move onto suggestions that while there may be public support for some individual ‘left-wing’ policies, voters are not willing to vote for lots of those policies at the same time.

This is a difficult thesis to test. Are we really expected to believe that Labour’s defeats in the last two general elections was due to the party offering voters too much of what they said they wanted? Or was there perhaps some more obvious reasons for the public twice rejecting a party led by Jeremy Corbyn?

Fighting the Last War

These questions highlight a wider problem. which is the tendency for political parties and commentators to fight the last war.

This could be seen clearly at the 2015 general election. In the run-up to the polls the overwhelming consensus among politicians, commentators and political scientists was that the UK was heading for another hung parliament, mirroring the result in 2010.

This assumption massively distorted coverage of the race and led to constant discussions about coalitions rather than any real analysis of what the Conservative party actually planned to do. The result was a working majority for David Cameron and the implementation of his largely unscrutinised pledge to hold a referendum on leaving the EU.

Much the same happened in 2017 when the overwhelming consensus was that Labour was heading for a big defeat under Jeremy Corbyn, much as they had under Ed Miliband in 2015. This again distorted coverage of the race and missed the actual story, which was that voters were far less keen on both Theresa May and her policy agenda than was widely assumed. The result was a hung parliament and years of complete Brexit stagnation, culminating in a Boris Johnson Government.

A similar tendency can be seen in analysis of the forthcoming general election.

Because of Labour’s heavy defeat in 2019 due to the party’s collapse in ‘red wall’ areas, the overwhelming consensus among both commentators and the Labour leadership is that the party must now switch to a socially conservative pro-Brexit position.

This consensus is maintained despite all of the evidence about how public opinion has significantly shifted in the intervening years.

One-Eyed politics

It is worth making clear that none of this is an argument for Labour staying in the same place as they were in 2019. After four defeats in a row, the party needed to change and some of what Starmer has done has undeniably improved its electoral standing.

However, any analysis about how Labour wins, not just the next general election, but subsequent general elections, needs to be based not just on what has happened in the past, but what is happening now and what is likely to happen in the future.

The tendency to believe that everything that has happened before will continue to happen in the future led to exactly the sort of complacency and lazy thinking that precipitated Labour’s collapse in its ‘red wall’ and Scottish strongholds in the first place.

To put it broadly, just because the Conservative Party has been the dominant political force in the post-war era, does not mean it will always continue to be so.

We are currently living through what has the potential to be the most politically tumultuous period of our lifetimes. Whether it’s the growing impact of climate change, declining living standards, multiple generations locked out of the housing market, post-Brexit economic stagnation, the impact of artificial intelligence on jobs, or the coming global migrant crisis, the political landscape in just five years time is likely to be incredibly different to the political landscape in 2019.

These changes are already leading to big shifts in the political makeup of the British electorate. As has been expertly detailed by the Financial Times itself there is already evidence that the UK’s population is becoming progressively less right-wing with each new generation, as the historic link between age and conservatism is broken.

These shifts can be be seen in the changing makeup of so-called “blue wall” seats, which were previously reliable Conservative strongholds but shifted decisively against the party in the recent local elections.

It can also be seen most clearly in London, where voters just a decade ago elected a Conservative mayor, but where they now register a 40-point lead for the Labour party.

Again, this is not to suggest that the UK electorate has somehow massively changed overnight and the Labour Party can simply sit back and reap the rewards. Where I have sympathy with Shrimsley’s argument is that I do believe that political parties are most successful when they have as broad appeal as possible. In order for Labour to win the next general election they will need to win both socially conservative voters in ‘red wall’ seats who switched their vote in 2019, as well as the increasingly liberal and younger voters now dominant in metropolitan areas such as London.

This will not always be possible and Labour does need to make some trade-offs. However, on some issues, there actually is already consensus across all regions and demographics.

One such area is the nationalisation of utilities, where recent public outrage over sewage spills and spiralling water bills demonstrates clearly why polling shows the public is so supportive of water nationalisation.

Were Keir Starmer really “shifting policy positions to match the values of target voters” as Shrimsley suggests, then he would now be strongly coming out in favour of a pro-nationalisation position. Yet rather than do this, Starmer has again pushed his party in the complete opposite direction to public opinion and abandoned his previous pledge to nationalise the industry.

The same can be said for increasing taxes on top earners, which Starmer previously supported in line with most of the population, but has now abandoned.

A similar trend can also be found on Starmer’s U-turn on Brexit, where polls show an increasing majority of voters now support rejoining the EU, but where Starmer has now taken the opposite stance.

Dupers’ Delight

In his piece Shrimsley argues that such “transformative” policies can only be pursued, if at all, once Labour is in Government.

“Starmer is learning what all successful Labour leaders have grasped,” Shrimsley writes.

“You can pursue a reformist agenda in office only once voters believe it is rooted in their values and that they can trust you to know when to rein in your radicalism.”

Aside from the implication that the Labour leader should essentially dupe the country into backing him, before revealing a much more progressive agenda, I am not convinced that this is a likely turn of events.

If Labour wins a majority next year on an essentially small-c conservative agenda, as Shrimsley suggests, then it is unlikely that he will simply abandon that in favour of a radically different agenda once in power.

While Starmer is no stranger to telling an electorate one thing before doing something completely different once he is in office, there is little evidence that this is what either Labour leader, or his team, are planning.

Indeed when looked at this way the real cause of Starmer’s decision to take a ‘conservative path to power’ becomes obvious. Rather than being based solely on shifting Labour’s values to match the public’s, Starmer’s shift is also quite clearly based on the beliefs and values of his own leadership team.

When Starmer ran for Labour leader he was surrounded by people from all wings of the party, including the soft and outright left. Most notably, former Corbyn aide Simon Fletcher was put in place as his campaign director.

Yet since winning that election, Starmer has instead surrounded himself with aides and advisors largely drawn from the right of his party. That such a leadership team would be opposed to all ‘left wing’ policies, even when some of them are shown to be overwhelmingly popular with the public is therefore not surprising.

There is nothing wrong with this of course. Keir Starmer is free to draw advice from wherever he pleases.

However, such essentially ideological choices do not require justification through false claims about England’s inherent conservatism or its its supposed innate opposition to left-wing ideas.

There was nothing innately Conservative about England when it rejected Labour in 2019, any more than there was something inherently socialist about England when it handed a landslide majority to Clement Attlee’s Government back in 1945. Each election is different to the last and each electorate is different to the last too.

As the Conservative Party is likely to soon discover, political parties succeed best when they move with the times and fail most when they don’t.

The big risk for Labour is that by being so determined to fight previous electoral wars, they too are missing the real shape of the electoral battles to come.

Folded with Adam Bienkov is an entirely reader-supported publication. To support independent journalism and help us hold the current and future governments to account, please sign up for a full paid subscription below.

The 2017 General Election is under-analysed. Almost airbrushed away. For Corbyn's supporters it was the "betrayal" of the Labour machine and right that denied him a small number of votes to win. For the Labour right it was a surprising recovery that made it impossible to remove Corbyn in a further coup.

The Conservatives were denied a majority and ended up in an unholy alliance with the DUP just to stay in power. Reducing Brexit to a nail biting minute by minute internal renegotiation of almost everything.

The 2019 election gave Johnson a majority with few more votes. The majority was a achieved via the fortunate business of Labour no longer having Scottish MPs, and the Conservatives morphing into a Brexit Party.

Key voters are that small group that make the small number seats flip. In a first past the post system, it means small moves can trigger massive changes. You can argue whether it's a good thing or a bad thing or a bad thing. The key point is it happens. That change was not a positive endorsement of the Conservatives but, with most elections, a vote against the alternatives.

If you have a General Election on one subject, Brexit, then the party that is least credible loses.

Since then, the new Brexit enthused Conservatives believe voters endorsed a right-wing platform. Starmer has removed the fear of Labour. It is now down to whether voters will vote against the Conservatives.

The poisonous role of the British press isn’t discussed. The election of a truly socialist government was (is) terrifying to the expatriate newspaper owners. They would have had to pay appropriate taxes on profits generated within this country. When the newspapers collectively told the public that Corbyn was an evil extreme left-winger who would sell the country to Russia, they obediently voted Conservative. The supreme irony is that the Conservatives are virtually owned by Russian interests. Also Starmer has, as you say, misunderstood the intent of the electorate.